How Did The Civil Rights Movement Change The World

Ceremonious rights movements are a worldwide series of political movements for equality before the police force, that peaked in the 1960s.[ citation needed ] In many situations they have been characterized by nonviolent protests, or accept taken the class of campaigns of ceremonious resistance aimed at achieving modify through nonviolent forms of resistance. In some situations, they have been accompanied, or followed, by civil unrest and armed rebellion. The process has been long and tenuous in many countries, and many of these movements did not, or have still to, fully achieve their goals, although the efforts of these movements have led to improvements in the legal rights of some previously oppressed groups of people, in some places.

The main aim of the successful ceremonious rights movement and other social movements for civil rights included ensuring that the rights of all people were and are equally protected by the law. These include simply are non limited to the rights of minorities, women's rights, disability rights and LGBT rights.

Northern Ireland civil rights movement

Northern Ireland is a role of the United Kingdom which has witnessed violence over many decades, known as the Troubles, arising from tensions between the British (Unionist, Protestant) bulk and the Irish (Nationalist, Cosmic) minority following the Partitioning of Republic of ireland in 1920.

The civil rights struggle in Northern Ireland tin exist traced to activists in Dungannon, led past Austin Currie, who were fighting for equal admission to public housing for the members of the Catholic community. This domestic upshot would not have led to a fight for civil rights were information technology not for the fact that being a registered householder was a qualification for local government franchise in Northern Ireland.[ commendation needed ]

In January 1964, the Campaign for Social Justice (CSJ) was launched in Belfast.[1] This organisation joined the struggle for better housing and committed itself to ending bigotry in employment. The CSJ promised the Catholic community that their cries would be heard. They challenged the government and promised that they would take their case to the Commission for Human Rights in Strasbourg and to the Un.[2]

Having started with basic domestic problems, the civil rights struggle in Northern Ireland escalated to a total-scale move that found its apotheosis in the Northern Republic of ireland Civil Rights Clan. NICRA campaigned in the late sixties and early seventies, consciously modelling itself on the American civil rights motion and using similar methods of ceremonious resistance. NICRA organised marches and protests to demand equal rights and an stop to discrimination.

NICRA originally had five main demands:

- one man, ane vote

- an stop to discrimination in housing

- an finish to discrimination in local government

- an terminate to the gerrymandering of district boundaries, which limited the effect of Cosmic voting

- the disbandment of the B-Specials, an entirely Protestant police reserve, perceived as sectarian.

All of these specific demands were aimed at an ultimate goal that had been the ane of women at the very kickoff: the cease of discrimination.

Civil rights activists all over Northern Ireland soon launched a campaign of civil resistance. There was opposition from Loyalists, who were aided by the Royal Ulster Law (RUC), Northern Ireland's constabulary force.[ commendation needed ] At this point, the RUC was over 90% Protestant. Violence escalated, resulting in the ascension of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) from the Catholic community, a group reminiscent of those from the War of Independence and the Ceremonious War that occurred in the 1920s that had launched a campaign of violence to end British rule in Northern Republic of ireland. Loyalist paramilitaries countered this with a defensive entrada of violence and the British authorities responded with a policy of internment without trial of suspected IRA members. For more 300 people, the internment lasted several years. The huge majority of those interned by the British forces were Cosmic. In 1978, in a instance brought by the authorities of the Ireland against the government of the Britain, the European Court of Homo Rights ruled that the interrogation techniques approved for use past the British army on internees in 1971 amounted to "inhuman and degrading" treatment.

The IRA encouraged Republicans to join in the movement for civil rights merely never controlled NICRA. The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association fought for the terminate of discrimination toward Catholics and did not take a position on the legitimacy of the country.[iii] Republican leader Gerry Adams explained later that Catholics saw that it was possible for them to have their demands heard. He wrote that "we were able to see an example of the fact that you didn't just have to take it, y'all could fight dorsum".[2] For an business relationship and critique of the movements for ceremonious rights in Northern Republic of ireland, reflecting on the cryptic link between the causes of civil rights and opposition to the wedlock with the United Kingdom, see the work of Richard English language.[4]

Ane of the most important events in the era of civil rights in Northern Ireland took place in Derry, which escalated the conflict from peaceful civil disobedience to armed conflict. The Boxing of the Bogside started on 12 August when an Apprentice Boys, a Protestant order, parade passed through Waterloo Place, where a large oversupply was gathered at the mouth of William Street, on the edge of the Bogside. Different accounts describe the starting time outbreak of violence, with reports stating that it was either an set on past youth from the Bogside on the RUC, or fighting broke out betwixt Protestants and Catholics. The violence escalated and barricades were erected. Proclaiming this district to be the Complimentary Derry, Bogsiders carried on fights with the RUC for days using stones and petrol bombs. The government finally withdrew the RUC and replaced it with the ground forces, which disbanded the crowds of Catholics who were barricaded in the Bogside.[5]

Bloody Sun, thirty January 1972, in Derry is seen by some equally a turning bespeak in the movement for civil rights. Fourteen unarmed Catholic civil rights marchers protesting against internment were shot expressionless by the British army and many were left wounded on the streets.

The peace procedure has made significant gains in recent years. Through open dialogue from all parties, a state of ceasefire past all major paramilitary groups has lasted. A stronger economy improved Northern Ireland's standard of living. Civil rights issues accept go less of a concern for many in Northern Ireland over the by xx years as laws and policies protecting their rights, and forms of affirmative action, have been implemented for all government offices and many private businesses. Tensions withal exist, just the vast majority of citizens are no longer affected by violence.

Canada's Quiet Revolution

The 1960s brought intense political and social change to the Canadian province of Quebec, with the election of Liberal Premier Jean Lesage after the death of Maurice Duplessis, whose government was widely viewed every bit corrupt.[6] These changes included secularization of the education and health care systems, which were both heavily controlled past the Roman Catholic Church, whose support for Duplessis and his perceived abuse had angered many Québécois. Policies of the Liberal government as well sought to give Quebec more economic autonomy, such equally the nationalization of Hydro-Québec and the creation of public companies for the mining, forestry, atomic number 26/steel and petroleum industries of the province. Other changes included the creation of the Régie des Rentes du Québec (Quebec Pension Plan) and new labour codes that fabricated unionizing easier and gave workers the right to strike.

The social and economical changes of the Placidity Revolution gave life to the Quebec sovereignty movement, as more and more Québécois saw themselves equally a distinctly culturally dissimilar from the remainder of Canada. The segregationist Parti Québécois was created in 1968 and won the 1976 Quebec full general election. They enacted legislation meant to enshrine French as the language of business organization in the province, while also controversially restricting the usage of English language on signs and restricting the eligibility of students to be taught in English.

A radical strand of French Canadian nationalism produced the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ), which since 1963 has been using terrorism to make Quebec a sovereign nation. In Oct 1970, in response to the abort of some of its members before in the year, the FLQ kidnapped British diplomat James Cross and Quebec's Minister of Labour Pierre Laporte, whom they later killed. The and so Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau, himself a French Canadian, invoked the State of war Measures Act, declared martial law in Quebec, and arrested the kidnappers by the cease of the year.

Movements for ceremonious rights in the United States

Movements for civil rights in the Us include noted legislation and organized efforts to cancel public and private acts of racial discrimination against African Americans and other disadvantaged groups betwixt 1954 and 1968, particularly in the southern United States. Information technology is sometimes referred to as the 2d Reconstruction era, alluding to the unresolved issues of the Reconstruction Era (1863–77).

Ethnicity equity issues

Integrationism

Subsequently 1890, the system of Jim Crow, disenfranchisement, and second class citizenship degraded the citizenship rights of African Americans, especially in the S. It was the nadir of American race relations. In that location were three master aspects: racial segregation – upheld by the United states of america Supreme Courtroom determination in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 –, legally mandated by southern governments—voter suppression or disfranchisement in the southern states, and private acts of violence and mass racial violence aimed at African Americans, unhindered or encouraged by government government. Although racial bigotry was nowadays nationwide, the combination of constabulary, public and private acts of bigotry, marginal economic opportunity, and violence directed toward African Americans in the southern states became known as Jim Crow.

Noted strategies employed prior to 1955 included litigation and lobbying attempts past the National Clan for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). These efforts were a authentication of the early American Civil Rights Movement from 1896 to 1954. However, past 1955, blacks became frustrated by gradual approaches to implement desegregation by federal and state governments and the "massive resistance" by whites. The black leadership adopted a combined strategy of direct activeness with nonviolence, sometimes resulting in irenic resistance and ceremonious disobedience. Some of the acts of nonviolence and civil disobedience produced crisis situations between practitioners and government government. The authorities of federal, state, and local governments ofttimes acted with an immediate response to end the crunch situations – sometimes in the practitioners' favor. Some of the dissimilar forms of protests and/or ceremonious defiance employed included boycotts, equally successfully expert past the Montgomery omnibus boycott (1955–1956) in Alabama which gave the motility one of its more than famous icons in Rosa Parks; "sit-ins", as demonstrated by 2 influential events, the Greensboro sit-in (1960) in Due north Carolina and the Nashville sit-ins in Nashville, Tennessee; the influential 1963 Birmingham Children'south Crusade, in which children were set upon by the local government with burn down hoses and assail dogs, and longer marches, as exhibited by the Selma to Montgomery marches (1965) in Alabama which at starting time was resisted and attacked past the state and local authorities, and resulted in the 1965 Voting Rights Act. The evidence of changing attitudes could also exist seen around the country, where small businesses sprang upwardly supporting the Civil Rights Movement, such as New Bailiwick of jersey's Everybody's Luncheonette.[seven]

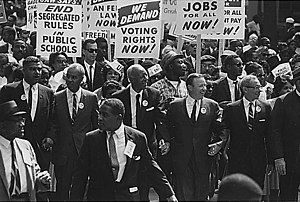

Besides the Children's Cause and the Selma to Montgomery marches, some other illustrious event of the 1960s Civil Rights Motility was the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in Baronial, 1963. It is best remembered for the "I Take a Dream" spoken language by Martin Luther King Jr. in which the speech turned into a national text and eclipsed the troubles the organizers had to bring to march forward. It had been a adequately complicated thing to join various leaders of civil rights, religious and labor groups. As the name of the march implies, many compromises had to exist made in order to unite the followers of then many different causes. The "March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom" emphasized the combined purposes of the march and the goals that each of the leaders aimed at. The 1963 March on Washington organizers and organizational leaders, informally named the "Big Six", were A. Philip Randolph, Roy Wilkins, Martin Luther King Jr., Whitney Immature, James Farmer and John Lewis. Although they came from dissimilar backgrounds and political interests, these organizers and leaders were intent on the peacefulness of the march, which had its own align to ensure that the result would be peaceful and respectful of the law.[8] The success of the march is nevertheless being debated, just ane aspect which has been raised was the misrepresentation of women. A lot of feminine civil rights groups had participated in the organization of the march, simply when it came to actual activity women were denied the right to speak and were relegated to figurative roles in the back of the stage. As some female participants noticed, the March tin be remembered for the "I Accept a Dream" oral communication only for some female activists information technology was a new enkindling, forcing blackness women non only to fight for civil rights but also to engage in the Feminist movement.[9]

Noted achievements of the Civil Rights Movement include the judicial victory in the Brown v. Board of Education case that nullified the legal article of "separate merely equal" and made segregation legally impermissible, and the passages of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, .[ten] that banned bigotry in employment practices and public accommodations, passage of the Voting Rights Deed of 1965 that restored voting rights, and passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1968 that banned discrimination in the sale or rental of housing.

Black Power move

By 1967 the emergence of the Black Ability motility (1966–75) began to gradually eclipse the original "integrated power" aims of the successful Ceremonious Rights Movement that had been espoused by Martin Luther Male monarch Jr. and others. Advocates of Blackness Ability argued for black cocky-determination, and asserted that the assimilation inherent in integration robs Africans of their common heritage and dignity. For example, the theorist and activist Omali Yeshitela argues that Africans have historically fought to protect their lands, cultures, and freedoms from European colonialists, and that any integration into the society which has stolen another people and their wealth is an act of treason.

Today, near Black Power advocates accept not changed their cocky-sufficiency argument. Racism nonetheless exists worldwide, and some believe that blacks in the U.s.a., on the whole, did not assimilate into U.South. "mainstream" civilization. Blacks arguably became even more oppressed, this time partially by "their own" people in a new black stratum of the eye class and the ruling class. Blackness Power's advocates by and large contend that the reason for this stalemate and further oppression of the vast majority of U.S. blacks is because Blackness Ability's objectives accept not had the opportunity to be fully carried through.

One of the nearly public manifestations of the Blackness Power motility took place in the 1968 Olympics, when two African-Americans, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, stood on the podium doing a Black Ability salute. This act is still remembered today every bit the 1968 Olympics Black Power salute.

Chicano Motility

The Chicano Movement occurred during the civil rights era that sought political empowerment and social inclusion for Mexican-Americans around a generally nationalist argument. The Chicano movement blossomed in the 1960s and was active through the tardily 1970s in diverse regions of the U.S. The movement had roots in the ceremonious rights struggles that had preceded it, adding to it the cultural and generational politics of the era.

The early heroes of the motion—Rodolfo Gonzales in Denver and Reies Tijerina in New Mexico—adopted a historical account of the preceding hundred and twenty-v years that had obscured much of Mexican-American history. Gonzales and Tijerina embraced a nationalism that identified the failure of the Us government to live upward to its promises in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. In that business relationship, Mexican Americans were a conquered people who only needed to reclaim their birthright and cultural heritage as part of a new nation, which later became known as Aztlán.

That version of the past did not, just accept into business relationship the history of those Mexicans who had immigrated to the United States. It too gave little attention to the rights of undocumented immigrants in the United States in the 1960s— which is not surprising, since immigration did non have the political significance it afterwards acquired. It was a decade later when activists, such as Bert Corona in California, embraced the rights of undocumented workers and helped broaden the motion to include their issues.

When the move dealt with practical issues in the 1960s, almost activists focused on the most immediate issues against Mexican Americans; unequal educational and employment opportunities, political disfranchisement, and constabulary brutality. In the heady days of the belatedly 1960s, when the pupil movement was active around the earth, the Chicano movement brought near more or less spontaneous actions, such equally the mass walkouts by loftier schoolhouse students in Denver and Due east Los Angeles in 1968 and the Chicano Moratorium in Los Angeles in 1970.

The movement was especially strong at the higher level, where activists formed MEChA, Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán, which promoted Chicano Studies programs and a generalized ethno-nationalist calendar.

American Indian Motion

At a time when peaceful sit-ins were a common protest tactic, the American Indian Move (AIM) takeovers in their early days were noticeably violent. Some appeared to be spontaneous outcomes of protest gatherings, but others included armed seizure of public facilities.

The Alcatraz Island occupation of 1969, although commonly associated with NAM, pre-dated the organization, but was a catalyst for its formation.

In 1970, AIM occupied abased property at the Naval Air Station about Minneapolis. In July 1971, it assisted in a takeover of the Winter Dam, Lac Courte Oreilles, and Wisconsin. When activists took over the Bureau of Indian Diplomacy Headquarters in Washington, D.C. in Nov 1972, they sacked the building and 24 people were arrested. Activists occupied the Custer County Courthouse in 1973, though law routed the occupation after a riot took place.

In 1973 activists and military forces confronted each other in the Wounded Knee incident. The standoff lasted 71 days, and two men died in the violence.

Asian American motion

Gender equity bug

If the period associated with start-moving ridge feminism focused upon absolute rights such every bit suffrage (which led to women attaining the correct to vote in the early on office of the 20th century), the period of the second-wave feminism was concerned with the issues such equally changing social attitudes and economic, reproductive, and educational equality (including the ability to have careers in addition to motherhood, or the right to choose not to have children) betwixt the genders and addressed the rights of female person minorities. The new feminist movement, which spanned from 1963 to 1982, explored economic equality, political ability at all levels, professional equality, reproductive freedoms, issues with the family, educational equality, sexuality, and many other issues.

LGBT rights and gay liberation

Since the mid-19th century in Federal republic of germany, social reformers have used the language of civil rights to argue confronting the oppression of same-sex activity sexuality, same-sex emotional intimacy, and gender variance. Largely, just not exclusively, these LGBT movements accept characterized gender variant and homosexually oriented people equally a minority grouping(s); this was the approach taken past the homophile move of the 1940s, 1950s and early 1960s. With the ascent of secularism in the Due west, an increasing sexual openness, women's liberation, the 1960s counterculture, the AIDS epidemic, and a range of new social movements, the homophile movement underwent a rapid growth and transformation, with a focus on building community and unapologetic activism which came to exist known as the Gay Liberation.

The words "Gay Liberation" echoed "Women'due south Liberation"; the Gay Liberation Front end consciously took its proper noun from the "National Liberation Fronts" of Vietnam and Algeria, and the slogan "Gay Power", as a defiant respond to the rights-oriented homophile movement, was inspired by Black Power and Chicano Power. The GLF'due south statement of purpose explained:

Nosotros are a revolutionary group of men and women formed with the realization that complete sexual liberation for all people cannot come about unless existing social institutions are abolished. Nosotros refuse society'southward attempt to impose sexual roles and definitions of our nature.

—GLF statement of purpose

GLF activist Martha Shelley wrote,

We are women and men who, from the fourth dimension of our primeval memories, have been in revolt confronting the sex-role construction and nuclear family unit structure.

Gay Liberationists aimed at transforming fundamental concepts and institutions of society, such every bit gender and the family. In order to achieve such liberation, consciousness raising and direct action were employed. Specifically, the word 'gay' was preferred to previous designations such as homosexual or homophile; some saw 'gay' as a rejection of the faux dichotomy heterosexual/homosexual. Lesbians and gays were urged to "come up out" and publicly reveal their sexuality to family, friends and colleagues equally a form of activism, and to counter shame with gay pride. "Gay Lib" groups were formed in Australia, New Zealand, Germany, French republic, the UK, the US, Italy and elsewhere. The lesbian group Lavander Menace was as well formed in the U.Due south. in response to both the male person domination of other Gay Lib groups and the anti-lesbian sentiment in the Women'south Move. Lesbianism was advocated as a feminist choice for women, and the commencement currents of lesbian separatism began to emerge.

By the tardily 1970s, the radicalism of Gay Liberation was eclipsed past a return to a more than formal motility that became known as the Gay and Lesbian Rights Movement.

Soviet Union

In the 1960s, the early on years of the Brezhnev stagnation, dissidents in the Soviet Union increasingly turned their attention ceremonious and eventually man rights concerns. The fight for ceremonious and homo rights focused on issues of freedom of expression, freedom of conscience, freedom to emigrate, punitive psychiatry, and the plight of political prisoners. Information technology was characterized by a new openness of dissent, a business organization for legality, the rejection of whatever 'underground' and violent struggle.[11] Information technology played a significant function in providing a common language and goal for many Soviet dissidents, and became a cause for diverse social groups in the dissident millieu, ranging from activists in the youth subculture to academics such every bit Andrei Sakhrarov.

Significantly, Soviet dissidents of the 1960s introduced the "legalist" approach of avoiding moral and political commentary in favor of close attention to legal and procedural bug. Post-obit several landmark trials of writers (Sinyavsky-Daniel trial, the trials of Alexander Ginzburg and Yuri Galanskov) and an associated crackdown on dissidents by the KGB, coverage of arrests and trials in samizdat (unsanctioned press) became more common. This activity somewhen led to the founding of the Chronicle of Current Events in Apr 1968. The unofficial newsletter reported violations of ceremonious rights and judicial process past the Soviet authorities and responses to those violations by citizens beyond the USSR.[12]

Throughout the 1960s–1980s, dissidents in the ceremonious and human rights movement engaged in a diverseness of activities: The documentation of political repression and rights violations in samizdat (unsanctioned press); private and commonage protest letters and petitions; unsanctioned demonstrations; an breezy network of common aid for prisoners of conscience; and, most prominently, civic lookout man groups appealing to the international community. All of these activities came at great personal risk and with repercussions ranging from dismissal from work and studies to many years of imprisonment in labor camps and being subjected to punitive psychiatry.

The rights-based strategy of dissent merged with the idea of human rights. The human rights movement included figures such as Valery Chalidze, Yuri Orlov, and Lyudmila Alexeyeva. Special groups were founded such equally the Initiative Group for the Defense of Human Rights in the USSR (1969) and the Commission on Human Rights in the USSR (1970). Though faced with the loss of many members to prisons, labor camps, psychiatric institutions and exile, they documented abuses, wrote appeals to international human rights bodies, collected signatures for petitions, and attended trials.

The signing of the Helsinki Accords (1975) containing human rights clauses provided civil rights campaigners with a new promise to use international instruments. This led to the creation of defended Helsinki Sentinel Groups in Moscow (Moscow Helsinki Group), Kiev (Ukrainian Helsinki Group), Vilnius (Lithuanian Helsinki Grouping), Tbilisi, and Erevan (1976–77).[xiii] : 159–194

Prague Spring

The Prague Spring (Czech: Pražské jaro, Slovak: Pražská jar, Russian: пражская весна) was a catamenia of political liberalization in Czechoslovakia starting on January 5, 1968, and running until August 20 of that twelvemonth, when the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact allies (except for Romania) invaded the land.

During World War II, Czechoslovakia fell into the Soviet sphere of influence, the Eastern Bloc. Since 1948 at that place were no parties other than the Communist Party in the country and it was indirectly managed by the Soviet Matrimony. Unlike other countries of Central and Eastern Europe, the communist take-over in Czechoslovakia in 1948 was, although as brutal as elsewhere, a genuine popular move. Reform in the state did non lead to the convulsions seen in Hungary.

Towards the end of World State of war II Joseph Stalin wanted Czechoslovakia, and signed an understanding with Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt that Prague would be liberated past the Ruby Regular army, despite the fact that the The states Army under Full general George S. Patton could have liberated the urban center before. This was important for the spread of pro-Russian (and pro-communist) propaganda that came right after the war. People still remembered what they felt as Czechoslovakia'due south expose by the West at the Munich Understanding. For these reasons, the people voted for communists in the 1948 elections, the final democratic poll to accept identify there for a long time.

From the centre of the 1960s, Czechs and Slovaks showed increasing signs of rejection of the existing regime. This change was reflected by reformist elements within the communist party by installing Alexander Dubček every bit party leader. Dubček's reforms of the political process within Czechoslovakia, which he referred to as Socialism with a human face, did not represent a complete overthrow of the former regime, every bit was the case in Hungary in 1956. Dubček's changes had broad support from the order, including the working class, but was seen by the Soviet leadership as a threat to their hegemony over other states of the Eastern Bloc and to the very condom of the Soviet Union. Czechoslovakia was in the middle of the defensive line of the Warsaw Pact and its possible defection to the enemy was unacceptable during the Cold War.

However, a sizeable minority in the ruling party, especially at higher leadership levels, was opposed to any lessening of the party's grip on club and actively plotted with the leadership of the Soviet Spousal relationship to overthrow the reformers. This group watched in horror as calls for multi-party elections and other reforms began echoing throughout the land.

Between the nights of August 20 and August 21, 1968, Eastern Bloc armies from 5 Warsaw Pact countries invaded Czechoslovakia. During the invasion, Soviet tanks ranging in numbers from 5,000 to seven,000 occupied the streets. They were followed by a large number of Warsaw Pact troops ranging from 200,000 to 600,000.

The Soviets insisted that they had been invited to invade the state, stating that loyal Czechoslovak Communists had told them that they were in need of "fraternal assistance against the counter-revolution". A letter of the alphabet which was establish in 1989 proved an invitation to invade did indeed exist. During the attack of the Warsaw Pact armies, 72 Czechs and Slovaks were killed (19 of those in Slovakia) and hundreds were wounded (up to September three, 1968). Alexander Dubček called upon his people non to resist. He was arrested and taken to Moscow, forth with several of his colleagues.

Movement for civil rights for Ethnic Australians

Australia was settled by the British without a treaty or recognition of the Indigenous population,[fourteen] consisting of Ancient Australian and Torres Strait Islander peoples. There were constraints on voting rights in some states until as late equally 1965 (Queensland), and state rights were hard fought for, with the granting of native title in Australia only coming into force federally in 1993. Cultural assimilation by forcible removal of Aboriginal children from their families took place until late in the 20th century. Similar other international civil rights movements, the push for progress has involved protests (See Freedom Ride (Australia) and Aboriginal Tent Embassy) and seen riots in response to social injustice, such as the 2004 Redfern riots and Palm Island riot.

While there has been significant progress in redressing discriminatory laws,[xv] Indigenous Australians proceed to exist at a disadvantage compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts, on key measures such as: life expectancy; infant bloodshed; wellness; imprisonment; and levels of pedagogy and employment. An ongoing government strategy chosen Closing the Gap is in identify in an attempt to remedy this.[sixteen]

See too

- Civil and political rights

- Protests of 1968

- Timeline of the civil rights movement

Notes

- ^ "Background to the Conflict". www.irelandseye.com . Retrieved 2019-07-17 .

- ^ a b Dooley, Brian. "2d Course citizens", in Black and Green: The Fight for Civil Rights in Northern Ireland and Black America. (London:Pluto Press, 1998), 28–48.

- ^ Dooley, Brian. "2d Class citizens", in Blackness and Greenish: The Fight for Civil Rights in Northern Ireland and Black America. (London:Pluto Printing, 1998), 28–48

- ^ Richard English, "The Coaction of Not-violent and Violent Action in Northern Ireland, 1967–72", in Adam Roberts and Timothy Garton Ash (eds.), Civil Resistance and Ability Politics: The Experience of Non-violent Action from Gandhi to the Nowadays, Oxford University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0-nineteen-955201-half-dozen, pp. 75–90. [1]

- ^ O'Dochartaigh, Niall. From Civil Rights to Armalites: Derry and the Birth of the Irish Troubles (Cork: Cork University Printing, 1997), 1–18 and 111–152.

- ^ "Web Folio Under Construction".

- ^ "Everybody's Luncheonette Camden, New Jersey". Archived from the original on 2011-05-23. Retrieved 2009-12-08 .

- ^ Barber, Lucy. "In the Great Tradition: The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, August 28, 1963," in Marching on Washington: The Forging of an American Political Tradition. (Berkeley: U of California Press, 2002), 141–178.

- ^ Height,Dorothy. "We wanted the voice of a woman to be heard": Black women and the 1963 March on Washington", in Sisters in the Struggle: African American Women in the Ceremonious Rights-Black Power Movement. Eds. Collier. Thomas, Bettye and 5.P. Franklin. (New York: NYU press, 2001), 83–91.

- ^ "Civil Rights Act of 1964". Archived from the original on 2010-10-21. Retrieved 2008-ten-02 .

- ^ Daniel, Alexander (2002). "Истоки и корни диссидентской активности в СССР" [Sources and roots of dissident activity in the USSR]. Неприкосновенный запас [Emergency Ration] (in Russian). ane (21).

- ^ Horvath, Robert (2005). "The rights-defenders". The Legacy of Soviet Dissent: Dissidents, Democratisation and Radical Nationalism in Russia. London; New York: RoutledgeCurzon. pp. 70–129. ISBN9780203412855.

- ^ Thomas, Daniel C. (2001). The Helsinki issue: international norms, human being rights, and the demise of communism. Princeton, North.J: Princeton University Press. ISBN0691048584.

- ^ "Lack of Treaty: Getting to the Heart of the Issue". Retrieved 13 Apr 2018.

- ^ "Timeline: Ethnic Rights Motility". Retrieved 13 Apr 2018.

- ^ "Indigenous disadvantage in Commonwealth of australia". Retrieved 13 April 2018.

Further reading

- Manfred Berg and Martin H. Geyer; Two Cultures of Rights: The Quest for Inclusion and Participation in Mod America and Germany Cambridge University Press, 2002

- Jack Donnelly and Rhoda E. Howard; International Handbook of Human Rights Greenwood Press, 1987

- David P. Forsythe; Man Rights in the New Europe: Problems and Progress University of Nebraska Press, 1994

- Joe Foweraker and Todd Landman; Citizenship Rights and Social Movements: A Comparative and Statistical Analysis Oxford University Printing, 1997

- Mervyn Frost; Constituting Human Rights: Global Civil Society and the Society of Autonomous States Routledge, 2002

- Marc Galanter; Competing Equalities: Law and the Astern Classes in India University of California Press, 1984

- Raymond D. Gastil and Leonard R. Sussman, eds.; Liberty in the World: Political Rights and Civil Liberties, 1986–1987 Greenwood Press, 1987

- David Harris and Sarah Joseph; The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and Great britain Constabulary Clarendon Printing, 1995

- Steven Kasher; The Ceremonious Rights Motility: A Photographic History (1954–1968) Abbeville Publishing Group (Abbeville Press, Inc.), 2000

- Francesca Klug, Keir Starmer, Stuart Weir; The Iii Pillars of Liberty: Political Rights and Freedoms in the Britain Routledge, 1996

- Fernando Santos-Granero and Frederica Barclay; Tamed Frontiers: Economic system, Gild, and Civil Rights in Upper Amazonia Westview Press, 2000

- Paul N. Smith; Feminism and the Tertiary Republic: Women's Political and Civil Rights in French republic, 1918–1940 Clarendon Printing, 1996

- Jorge Thou. Valadez; Deliberative Democracy: Political Legitimacy and Self-Determination in Multicultural Societies Westview Press, 2000

External links

- We Shall Overcome: Celebrated Places of the Civil Rights Motility, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage at Travel Itinerary

- A Columbia University Resource for Instruction African American History

- Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Global Freedom Struggle, an encyclopedia presented past the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Instruction Institute at Stanford University

- Altman, Andrew. "Civil Rights". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Global Freedom Struggle ~ an online multimedia encyclopedia presented past the King Constitute at Stanford Academy, includes information on over 1000 Civil Rights Movement figures, events and organizations

- "CivilRightsTravel.com" ~ a visitors guide to key sites from the Civil Rights Movement

- The History Aqueduct: Civil Rights Movement

- Civil Rights: Beyond Black & White – slideshow past Life magazine

- Civil Rights Digital Library from the Digital Library of Georgia

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Civil_rights_movements

Posted by: prowellworly1971.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Did The Civil Rights Movement Change The World"

Post a Comment